Cussin’ and Swearin

The term ‘transhumance’ refers to the practice, in mountainous regions, of bringing grazing animals such as cattle, goats, and sheep to higher areas during the summer months, where they can pasture under the watchful gaze of their herders.

As well as the agricultural benefits, transhumance was traditionally associated with specific forms of folk music and lore derived from the long days and nights the herders spent in the highlands.

In mountainous areas characterised by small settlements that were often quite cut off from one another during the winter months, transhumance was also a way for communities to come together, as herders from different areas would meet and interact in the meadows.

In many areas, the contact between these herders speaking the same or similar dialects provided something of a bulwark against the encroachment of the national languages that have tended in recent centuries to reduce linguistic diversity.

Transhumance is still practised today in some areas, but as motorways and other modern forms of infrastructure now often bisect former agricultural territories and transhumance routes, it is more complicated and less common than it once was.

It is still, however, an interesting linguistic field (pun intended!). Increasingly in southern Europe, where transhumance was once very widespread, herding is provided by migrants from North Africa and elsewhere, who bring their languages with them, altering the landscape of communication.

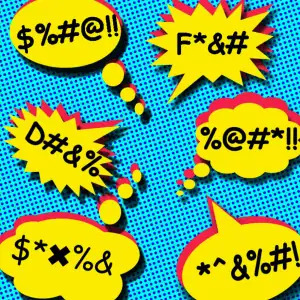

In 1972, Italian singer Adriano Celentano was fed up with the impact of American popular culture on Italian music. To make a point, he composed a song titled Prisencolinensinainciusol, whose lyrics are entirely composed of gibberish that, to Italian ears, sounded like American English. The song, in a genre combining funk, disco and a precursor of hip hop, was a massive hit in several European countries. Celentano claimed to have invented the rap genre with this song and stated that he had been inspired by the Biblical story of the Tower of Babel, among other things.

Thanks in large part to YouTube, Prisencolinensinainciusol has had a long second life, with its video racking up millions of views, and TV and radio producers using it in their soundtracks.

Photo Source: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0147983/

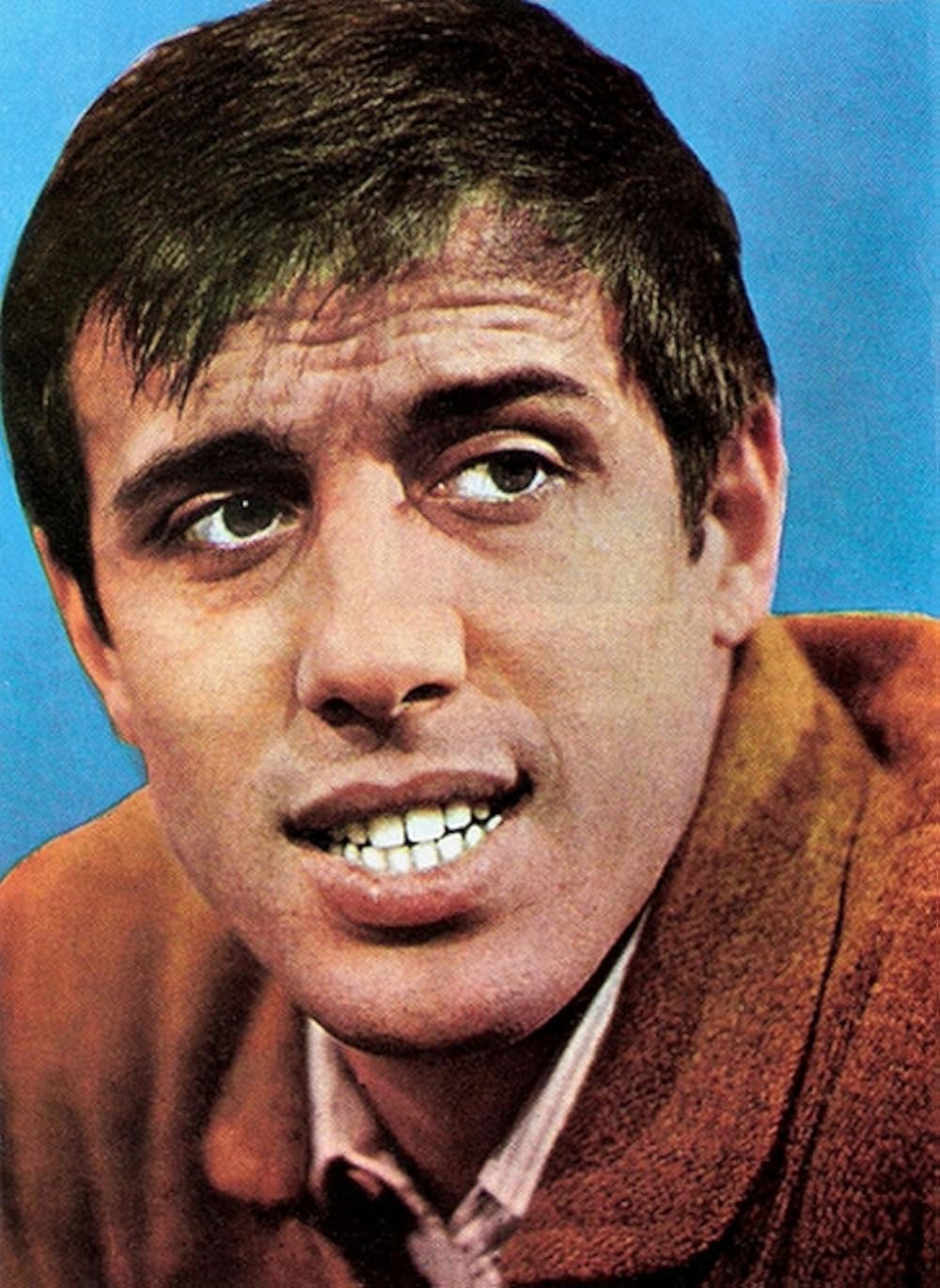

There are only a few recorded instances in history of an individual member of a pre-literate society creating an original writing system from scratch. One is the example of Sequoyah, a Cherokee man impressed by the concept of rendering speech in written form, which he first encountered through contact with European settlers. Seeing that their ability to write gave white settlers an advantage over the Cherokee, Sequoyah decided to right this imbalance.

While many pre-literate societies become literate in their own language by adopting an existing writing system – for instance, the Roman alphabet – Sequoyah developed his own, which he finalised in 1821.

Having toyed with pictographs at first, Sequoyah ultimately developed a symbol for each syllable in the Cherokee language. Using printed materials as a reference, including the Bible, he developed a syllabary of 85 symbols, many of them adapted from English, Greek and Hebrew letters – but representing completely different sounds.

Initially, Sequoyah’s work aroused suspicion and he was arrested by Cherokee authorities, but when they saw how he could use writing to communicate with his daughter, whom he had taught how to read, the Cherokee people became enthusiastic about the new writing system. Literacy spread rapidly among the Cherokee, with up to 100% of them literate by around 1846; a higher rate than among Europeans settling in North America in the same time period.

Sequoyah’s work would influence many others around the world. It is believed, for example, that when a literate Cherokee emigrated to Liberia, he inspired speakers of Bassa to develop their own syllabary, and several other West African cultures did likewise.

Photo Source: https://www.native-languages.org/cherokee_alphabet.htm

Languages come into being and are disseminated in various ways. Obviously, the languages we speak, and how we speak them, are influenced by our family and cultural backgrounds, the education we receive, and the people we meet throughout our lives.

Some researchers also believe that language may be affected by climate. Linguistic anthropologist Caleb Everett points out that different sounds can be easier or harder to make depending on the climatic conditions. For example, some sounds are much harder to make if your vocal cords are very dry, which is more likely to be the case somewhere with a hot, arid climate. According to Everett’s research, languages that developed in places with very dry climates use fewer vowel sounds than languages that developed in places with high levels of humidity, and languages that come from places at high altitude use a higher number of ejective consonants, which are explosive sounds made when the vocal cords are closed.

Nowadays, human populations are extremely mobile, so cultural influences are likely to be more important than climate into the future. Nonetheless, this unusual, intriguing and emerging field of linguistic research opens up many avenues for future investigation, including the possibility that, over time, climate change may have a noticeable impact on how we talk.

We speak just about every language imaginable here at 101translations. Get in touch to learn how we can help you with your translations needs at 👉https://101translations.com/

#Climate #ClimateChange #CulturalConnections #CalebEverett #ClimateConditions #DryClimates #Facts #DidYouKnow #Humidity #101Translations #LanguageExperts #Culture

Photo Source: https://wonderopolis.org/wonder/what-is-climate-change

Prior to the conquest and colonisation of North America, the areas now known as Canada, northern Mexico and the United States were home to a large number of indigenous cultures, each with its own language. Many of those languages were not closely related, and while many people spoke several of them, it was often necessary to communicate with individuals from very different linguistic backgrounds.

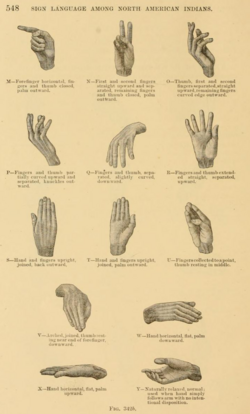

To solve this language dilemma, these indigenous nations developed a form of signing, known as ‘Plains Indian Sign Language’, ‘Hand Talk’, and by several other names. Historically, it was used for international commerce and diplomatic relations, much as Latin was once used in Europe. It combined simple gestures – such as pointing upwards for ‘up’ – with complex hand-movements denoting abstract concepts. It also existed in a written form comprising petroglyphs, pictographs and hieroglyphs that marked territory and provided information about local water sources and other crucial information.

Today, Plains Indian Sign Language is – like many North American languages – endangered, but a recent resurgence in interest signals that it may still have a future.

Photo Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plains_Indian_Sign_Language

If you’re ever tempted to doubt the power of language to influence behaviour, you need only consider the tragic case of the first known relationship between literature and mass suicide.

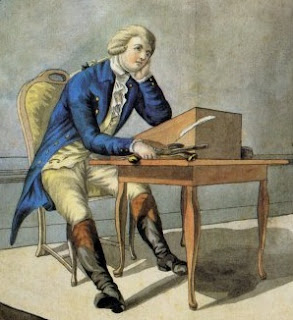

In 1774 – at a time when fiction-writing and reading were ever-more popular – Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published his novel, The Sorrows of Young Werther. With its overblown emotions and dramatic plot, it was a runaway bestseller, particularly among young adult readers.

Young men all over Europe imitated the protagonist by dressing in his trademark yellow trousers and blue jacket, and some of them were even inspired by the fictional character’s sad death (suicide by self-inflicted gunshot after being rejected by the woman he loved) to kill themselves using similar means. Panic-stricken parents rallied, and the book – as well as the outfit – was even banned in some places, while debate raged about whether or not impressionable young people should even be allowed to read fiction at all.

Today, social contagion, particularly when it relates to tragic or unfortunate outcomes, is often attributed to the media. Researchers in the area still refer to the ‘Werther effect’ in discussions of copycat suicide with a connection to language and media.

Photo Source: https://andrewbarger.blogspot.com/2017/04/review-of-sorrows-of-young-werther.html

People caring for infants often instinctively use a specific type of speech, commonly known as ‘baby talk’ or, by researchers, as ‘child-directed speech’. It is notably higher in pitch, with a slower rate of speech and a more melodic deliverance than that typically used by adults, with an emphasis given to the enunciation of vowels, and longer pauses than is typical in spoken language.

People using baby-talk might sound irritating to the unsentimental bystander, but they haven’t actually gone goo-goo/ga-ga. Research shows that babies are more responsive to child-directed speech, that they focus more intently on and interact more with adults speaking this way, and even that it enhances their cognitive development, including speech acquisition!

Photo Source: https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2020/03/babies-love-baby-talk-world

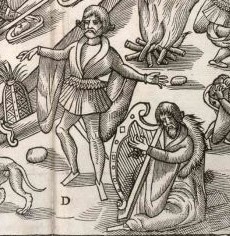

Bardic poets occupied a very important role in Irish society from the pre-Christian period until the seventeenth century, with many texts surviving. Bards used highly formalised, complex poetic language to memorise and retell the history and traditions of the tribe or area they worked in, including detailed genealogies and life-stories of the elite.

In order to become a bard, would-be scholars attended special schools that were often restricted to particular families, with students subjected to arduous training, which included having to commit lengthy poems to memory, as well as writing them down.

Bardic poets were held in such high esteem that when they cursed their employers’ adversaries, it was believed that their words could even have the power to do harm.

Modern Irish people still admire and respect both poets and members of the general public who are good at using words to praise their allies or declaim their foes. While taken less seriously than before, inventive cursing still plays a role in modern Irish discourse.

Photo Source: https://meathhistoryhub.ie/o-dalaigh-bardic-poets-their-poetry-and-their-patrons/

In Slavic tradition, the word ‘zagovory’ refers to verbal incantations thought to cast spells. The word itself means roughly ‘that which is performed with speech’. Practitioners used particular words, pronounced in a special way, as they performed their rites.

The tradition of zagovory is based on pre- or non-Christian beliefs, with frequent reference to sacred trees and to celestial bodies such as the sun and moon. It was an integral part of life in Slavic regions until the religious authorities decided to crack down on it from the mid-seventeenth century onwards. In response, the tradition adopted Christian themes and imagery, with the names of figures such as Jesus frequently invoked in more recent iterations of the tradition.